In 2015, Public Health England (PHE) published an evidence summary exploring the relationship between dental caries and obesity. This review analysed local authority-level data from cross-sectional surveys conducted by the National Dental Epidemiology Programme and the National Child Measurement Programme. It concluded that children living with obesity had higher levels of dental caries compared to those of a healthy weight. These findings reinforced previous research demonstrating a greater prevalence of tooth decay in children with obesity.

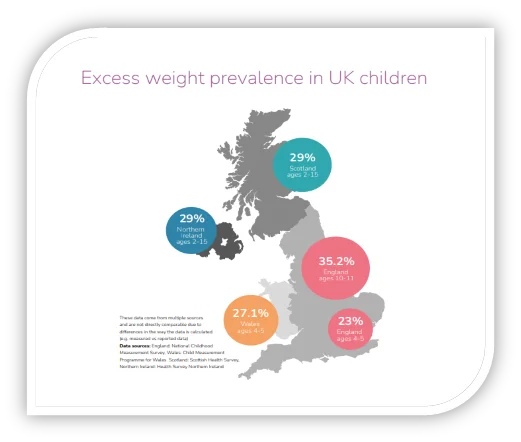

Across all population groups, particularly among children, excessive sugar consumption remains a pressing concern. High sugar intake contributes to excessive calorie consumption and, over time, weight gain and obesity. Obesity rates among 10–11-year-olds in England rose from 17.5% in 2006/07 to 21% by 2019/20 (Turning the Tide). Around one in eight children aged between two and 10 in England are obese, (NHS survey Sep 2024)

New statistics show around one in seven children (15%) aged between two and 15 were obese in 2022 – similar to 2019 (16%). Obesity rates in 2022 were 12% among those aged between two and 10, and 19% in those aged between 11 and 15.

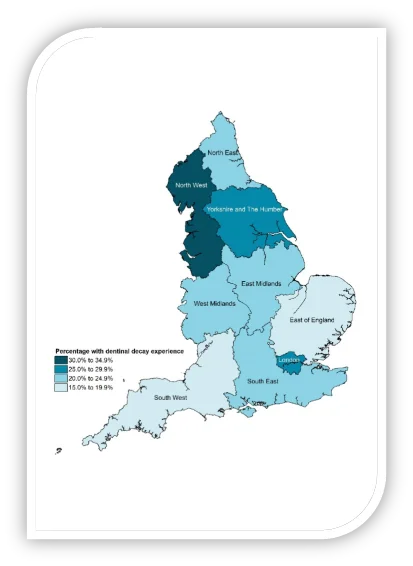

High sugar consumption is also a well-established risk factor for dental caries—the most common oral disease affecting children and young people in England. Yet, dental caries is largely preventable. According to the National Dental Epidemiology Programme for England (2017), almost a quarter (23.3%) of 5-year-olds had experienced tooth decay, with significant oral health inequalities across socioeconomic groups. Alarmingly, nearly 90% of hospital-based tooth extractions in children aged 0 to 5 are due to preventable decay. In fact, tooth extraction remains the most common hospital procedure in 6 to 10-year-olds.

More recently, the Royal College of Surgeons of England reported that tooth decay was the leading cause of hospital admissions among 5 to 9-year-olds. In 2023/24 alone, 19,381 children in this age group were admitted to hospital due to dental caries.

Map 2: Prevalence of experience of dentinal decay in 5 year olds in England by region, 2022

We are in the midst of a crisis in children’s oral health. Across the UK, children are being admitted to hospitals for general anaesthetics simply to have decayed teeth removed—an outcome that is preventable in the vast majority of cases. It is deeply concerning that we are continuing to see such high numbers of paediatric dental procedures under general anaesthetic for a disease that is almost entirely avoidable. Prevention must be our main strategy in tackling both child obesity and dental decay.

As dental and medical professionals, we must ask ourselves: are we doing enough to support, educate, and empower families to give their children a healthier start?

Adult obesity trends are similarly concerning. In 1993, 13% of men and 16% of women in England were classified as obese. By 2019, those figures had more than doubled to 27% and 29%, respectively (Turning the Tide). The costs of obesity to the NHS are significant: £6.1 billion was spent on obesity-related ill health in 2014/15, with projections estimating this will rise to £9.7 billion annually by 2050.

So, how do we move forward? How can we shift attitudes toward diet and prevention?

As someone who grew up in Germany, I was unfamiliar with the ubiquity of sugary drinks and desserts that are still commonplace in UK children’s diets. When my daughter attended nursery, I was alarmed to find squash freely available throughout the day. After raising concerns with the nursery director, she acted swiftly to replace squash with water. Sometimes, small interventions can make a big difference.

This highlights the power of education and the need for consistent messaging. We must rethink children’s diets to effectively prevent both obesity and tooth decay.

The increasing presence of ultra-processed foods in children’s diets is also cause for concern. My patients’ diet histories often include items such as sugary breakfast cereals, packaged white bread and pastries, flavoured yoghurts, crisps, sweets, cakes, fizzy drinks, and milkshakes. These foods not only contribute to obesity but also compromise oral health.

According to the Darcy Report (2024), the number of children with life-threatening and life-limiting conditions linked to obesity has increased by 250% between 2001 and 2018, with over 1.2 million children now living with obesity-related complications.

Funding must include not solely treating disease but preventing it too. Strategy documents such as Turning the Tide, which address adult obesity are necessary to identify the changes necessary to address adult obesity and we need further targeted approaches to address children’s general and oral health. Cultural and dietary habits must be addressed from infancy. This includes guidance on breast feeding and formula feeding, when to wean, and the importance of oral hygiene advice and early dental visits to introduce preventative measures.

For teenagers and older children, policies must also reduce the accessibility and marketing of unhealthy foods and sugary drinks. Social media could play a vital role in delivering public health messages targeted at this demographic.

Tooth decay is preventable. Regular brushing with fluoridated toothpaste, reduced sugar intake, and routine dental visits are key. However, access to NHS dental care remains an ongoing challenge that must be addressed. Primary dental care plays a crucial role in delivering preventative advice, and ensuring access for all children is essential to improving outcomes.

We need coordinated national action. The health of the next generation depends on it.